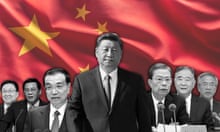

Promotion of historian who spearheaded rehabilitation of the Qing period prompts speculation that the past is being reinterpreted to bolster President Xi.

Manchu men, from the group that ruled China during the Qing dynasty, circa 1901. Photograph: Granger/Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Manchu men, from the group that ruled China during the Qing dynasty, circa 1901. Photograph: Granger/Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

By Verna Yu

–

At the height of the Qing dynasty, the Chinese empire was one of the great powers of the world. Its territory spanned all the way to Inner Asia and its economic prosperity and military might was the envy of the world.

But despite its success, rampant corruption, weak governance, internal revolts and foreign invasion led to the decline of its national power and its eventual collapse. The beginning of the 20th century would mark the end of China’s centuries-long dynasties, ruled over by emperors.

For decades, the Qing imperial dynasty’s isolationist policies have been widely blamed for the country’s downfall, but that history is now being revisited.

The recent promotion of a historian – who spearheaded a rehabilitation of the period – to the highest levels of Chinese society has led to speculation that the past is being reinterpreted to bolster President Xi Jinping’s ideological and political authority.

Historian Gao Xiang was appointed president, as well as the more powerful role of secretary of the Communist party, at the influential Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) just before the new year. The CASS is the top national research institution that formulates ideology and advises leaders on policy-making.

At the 2019 launch of the Chinese Academy of History, of which Gao is also president and party chief, Xi stated its mission was to push a historical narrative with “Chinese characteristics”.

Chen Daoyin, a former associate professor at Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, says Cass is not so much an academic institution but a body to formulate party ideology to support the leadership. “[Xi] needs experts to reinterpret Chinese history to bolster his credibility,” Chen says.

Xi regards history as a highly contentious issue and has repeatedly emphasized the importance of upholding the party’s own version of the past. Since he took power, authorities have pulled out all the stops to suppress unorthodox versions of history that they fear would tarnish the image of the party and threaten its legitimacy.

In 2013, an internal Communist party edict known as Document No 9 denounced “historical nihilism” among the seven supposedly subversive influences on society. In 2016, the authorities forcibly took over the management of a political magazine, Yanhuang Chunqiu, which often contested official versions of history with eyewitness accounts. In 2017, the country legislated against defaming the Communist “heroes and martyrs” to punish those who challenge the official history.

The Chinese Communist party has a record of manipulating historical records as well. Photos in state press were often altered to cut out purged individuals and historical documents were tampered with to suit the latest political needs.

Gao, an expert on China’s two last imperial dynasties – Ming and Qing, which ruled from late 14th to the early 20th centuries – is known for his loyalty to Xi and his defense of Xi’s ideology and policies.

Last summer, an article written by a panel led by Gao at the Chinese Academy of History created a furor. Readers saw it as an oblique justification of China’s isolationist foreign policy amid the Covid lockdowns and escalating tensions with the west.

The article was a defense of biguan suoguo (“closing and locking up of the country”), an isolationist policy implemented by the imperial rulers of the Ming and Qing dynasties that is widely blamed for China’s decline in the late 19th century. The article contends that the popular depiction of the closed-door policy as backwards and barbaric is a “western-centric” historical narrative.

It argues that the policy should be seen in historical context as a self-defense strategy to fend off the “threatening aggressive western colonial forces”. A video clip embedded in the official social media post highlights the message of China under siege under western colonialism with images of warships and colonial invaders in 19th-century costume.

Gao has also penned numerous articles in the state press in support of Xi’s rhetoric and his vision of the “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. Last week, an article by Gao touted on the website of CASS insisted that “one cannot stray from the party’s firm leadership and the firm discipline for a moment … the nation can only be strong when the party is strong”.

Prof Steve Tsang, the director of the SOAS China Institute, says Xi’s appointment of Gao was not due to his academic merits but, rather, his political loyalty. His appointment was in the same vein as Xi’s promotion of his allies to the party’s top political decision-making body at the 20th party congress last year, he says.

“Under Xi, be it history, literature or music, everything has to serve the purpose of patriotism, and Xi personifies the state … If history doesn’t dovetail with Xi’s rhetoric, that’s unpatriotic.”

The year is 2033. Elon Musk is no longer one of the richest people in the world, having hemorrhaged away his fortune trying to make Twitter profitable. Which, alas, hasn’t worked out too well: only 420 people are left on the platform. Everyone else was banned for not laughing at Musk’s increasingly desperate jokes.

In other news, Pete Davidson is now dating Martha Stewart. Donald Trump is still threatening to run for president. And British tabloids are still churning out 100 articles a day about whether Meghan Markle eating lunch is an outrageous snub to the royal family.

Obviously I have no idea what the world is going to look like in a decade. But here’s one prediction I feel very confident making: without a free and fearless press the future will be bleak. Without independent journalism, democracy is doomed. Without journalists who hold power to account, the future will be entirely shaped by the whims and wants of the 1%.

A lot of the 1% are not big fans of the Guardian, by the way. Donald Trump once praised a Montana congressman who body-slammed a Guardian reporter. Musk, meanwhile, has described the Guardian, as “the most insufferable newspaper on planet Earth.” I’m not sure there is any greater compliment.

I am proud to write for the Guardian. But ethics can be expensive. Not having a paywall means that the Guardian has to regularly ask our readers to chip in. If you are able, please do consider supporting us. Only with your help can we continue to get on Elon Musk’s nerves.

Arwa Mahdawi

Columnist, Guardian US

–

Topics

Most viewed

- –

- –

- –

- –

- –