In rousing new historical drama Chevalier, the story of Joseph Bologne, often crudely referred to as ‘Black Mozart’, is finally given the spotlight it deserves.

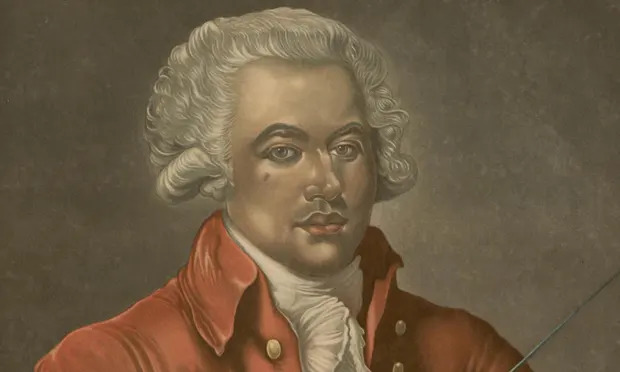

‘The Black contribution to classical music has always been very robust and very diverse’ … portrait of Joseph Bologne, c 1780. Photograph: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy

‘The Black contribution to classical music has always been very robust and very diverse’ … portrait of Joseph Bologne, c 1780. Photograph: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy

–Music

–

It is the moment that Amadeus finally knows how Salieri felt. Strutting with arrogance, Mozart is challenged to a violin duel and upstaged by a precocious rival. His name? Joseph Bologne, AKA the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, AKA young, gifted and Black.

Whether this showdown ever took place is doubtful but it makes for a playful opening to Chevalier, a new film based on the life of the long-overlooked classical composer who was also a champion fencer, as devastating with the foil as the fiddlestick.

The movie, directed by Stephen Williams (Watchmen) and written by Stefani Robinson (Atlanta), traces Bologne from his origins on a slave plantation to his acquaintance with Marie Antoinette, the last queen of France before the revolution.

Bologne – played by Kelvin Harrison Jr, who studied violin seven hours a day – was born in 1745 on the island of Guadeloupe. His parents were Georges de Bologne Saint-Georges, a wealthy French plantation owner, and an enslaved 16-year-old from Senegal, known as Nanon, who would eventually live in France as a free woman.

Bologne moved to France as a child. Julia Doe, assistant professor of music at Columbia University in New York, explains: “Pragmatically speaking, his father had to flee Guadeloupe to escape murder charges. More generally, it was not uncommon for members of the French colonial elite to send their children, including mixed race children, to be educated in the metropole.”

Bologne studied music, mathematics, literature and fencing at La Boëssière Academy. Doe continues: “In his early teenage years Bologne enrolled at this prestigious fencing academy of a Parisian master at arms and, because fencing was a physical art associated with the historical French nobility, the skills and connections that he developed at this academy would pave his entry into the highest circles of courts and capital.

“Once he arrives in Paris, he becomes this truly remarkable figure. One of his close friends wrote a biographical notice a few decades after his death and, unlike other more famous composers of this period, it’s very clear that music was just one facet of Bologne’s personal and professional identity. His friend praises his upstanding character and his accomplishments as a swordsman, a dancer, a swimmer, an ice skater, and so on. It’s truly extraordinary.”

Bologne gained renown as an undefeated fencer and lauded as a dancer, equestrian and fashion trendsetter. John Adams, the second US president, declared him “the most accomplished man in Europe in riding, shooting, fencing, dancing and music”.

People flocked to his violin concerts as he pushed the instrument to its limits. As a composer, Bologne wrote pioneering string quartets and helped establish the symmetry and melody of the baroque era.

Doe continues: “By the mid-1760s, his name starts to appear as a dedicatee of violin pieces published by other virtuosos in Paris, indicating that his talents were beginning to be recognized. Then within just a few years he was quite firmly established on the Parisian musical scene.”

Bologne’s artistic accomplishments fell into four main areas: he worked in high-profile positions as an orchestral player, soloist and ensemble director; he was commissioned to write operas for Parisian theaters; he appeared at musical salons of the noble and wealthy; he published works for the flourishing French print market.

Doe adds: “His wide output for those venues included all of the most fashionable genres of this day: violin concertos, operas, songs and chamber music, among other works. His music was quite well-regarded.”

It may have influenced other composers including his contemporary Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. But the dueling violins portrayed in the movie Chevalier are likely to be some artistic license on the part of Hollywood.

–

Doe says: “A general relationship between these two very precocious musicians is certainly plausible. Mozart traveled to Paris in 1778 and, once there, he associated with the extended networks of a very powerful man, the Duke of Orleans, who was also the patron of Bologne. Mozart was writing music for various concert series at the capital with which Bologne had relationships. It seems likely that they met and, if they didn’t meet, they surely knew of each other’s work.

“Musical scholars find the comparative label that is sometimes used – ‘the Black Mozart’ – to be far too reductive because it’s very clear that Bologne’s remarkable life deserves to be studied in its own right. While their pieces rely on a common stylistic vocabulary just because they were both writing for courtly context in the 18th century, their music isn’t that similar.”

Bologne was made an officer of the King’s Guard. King Louis XV named him Chevalier de Saint-Georges, after his father’s title, even though France’s Code Noir barred him from officially inheriting the title because of his African ancestry.

Indeed, for all his stardom, Bologne was not granted equal rights. While France’s Enlightenment philosophers opposed slavery, he knew well that the monarchy supported it.

As he stood on the verge of the ultimate prize, becoming the first person of color to head the Paris Opéra, a trio of divas intervened, declaring they would never “submit to orders of a mulatto”.

Doe says: “The Paris Opéra was the most prestigious French cultural institution at the time. This was a crown-supported company that produced tragic operas. The precise chain of events is not archivally recoverable in that the opera was in a state of disarray at the time, but it does seem that this failure was racially motivated.

“A periodical reported that several of the company’s star singers had petitioned the queen, whom Bologne knew quite well, to thwart his candidacy, refusing to work under the leadership of a mixed race musician.”

–

The queen in question was Marie Antoinette, who had arrived in France as a 14-year-old Austrian princess. Bologne was recruited to teach her music. But in his hour of need at the Paris Opéra, she did not lift a finger to help him.

Snubbed, Bologne turned from music to social change, becoming an abolitionist and soldier of the French Revolution. He led France’s first all-Black regiment, 1,000 men strong.

Few details are known of his private life but he was rumored to have been especially close with Marie-Josephine de Comarieu, wife of the Marquise de Montalembert – an intrigue that is a gift to the makers of the movie.

Doe comments: “There are many references in gossipy periodicals of the time that he was very well liked by aristocratic women but nothing fully substantiated. I suspect that’s quite fictional but the gossip about the love of aristocratic women for him was something that was circulating in the 18th century.”

Bologne died in 1799 of an ulcerated bladder, unmarried and with no known children. But his music, which includes references to traditional songs from Guadeloupe, has been brought back to life in recent years by orchestras and opera houses around the world. His chamber opera The Anonymous Lover was recently staged by the LA Opera.

Marcos Balter, a Black composer and professor of musical composition at Columbia University, says: “He is crawling his way out of being a curiosity. One would hope that someone of his importance and relevance would not only now be ‘rediscovered’. But do I think that he gets enough performance given his importance in the history of classical western music? No. It’s better but better doesn’t mean good.”

Now Chevalier, released on Friday, aims to put Bologne back in the middle of the cultural conversation – and repudiate the notion that classical music was long the sole preserve of dead White European males.

Balter, 49, comments: “The Black contribution to classical music has always been very robust and very diverse. It’s not that there is a scarcity. There is a myth of scarcity and there is a lack of information about it.

“More often than not contributions by folks who are not from what is perceived as the Eurocentric legacy or people with a specific profile tend to be minimized or sometimes completely erased from history. People like myself, of course, would feel a little bit like outsiders when sometimes history actually proves it otherwise, that we have been an integral part of that history, it’s just the way that it was retold removed us from it.”

–

This was the case with Bologne. “This was a main figure in the history of classical music. When we think of the classical period, he was one of the forefront names in the development of many of its strengths, musically and stylistically. You don’t see that in history books.

“If you do your research you see that he was one of the first composers to engage with writing string quartets, with thinking of new ways of how to develop music that were then picked up by other composers that we consider as masters.

“Even as a conductor and a commissioner, he was responsible for commissioning major works like the Haydn symphonies. But when we study this repertoire, his name is nowhere to be seen. Then one has to ask oneself, why has this person specifically been erased from these facts?”

In 2020 Balter wrote a New York Times opinion column headlined His Name Is Joseph Boulogne, Not ‘Black Mozart’. The new film seems sure to invite fresh comparisons between the composers as well as between itself and Miloš Forman’s Oscar winning Amadeus from 1984.

Balter says: “Mozart is a tremendous composer. I adore Mozart’s music so my reaction to Mozart as an artist and as an influence in history remains intact. He is a great figure. Saying that Bologne is a great figure does not mean that Mozart wasn’t. It only means that we should not talk about this artist as the shadow of this other one. It’s not an either/or. It’s an and.”

- Chevalier is out in US cinemas on 21 April and in the UK on 9 June

–