An investigation found criminal gangs using sham bank accounts and secret online marketplaces to steal from almost anyone – and little being done to combat the fraud.

Published:

In January 2020, Debi Gamber studied a computer screen filled with information on scores of check deposits. As a manager for eight years at a TD Bank branch in the Baltimore suburb of Essex, she had reviewed a flurry of account activity as a security measure. These transactions, though, from the ATM of a tiny TD branch nestled in a nearby mall, struck her as suspicious.

Digging deeper, she determined that the same customer service representative, Diape Seck, opened at least seven of the accounts, which had received more than 200 church check deposits. Even fishier, the purported account holders used Romanian passports and drivers’ licenses to prove their identities. Commercial bankers rarely see those forms of ID. So why were all these Romanians streaming into a small branch located above a Marshall’s clothing store?

Suspecting crimes, Gamber submitted an electronic fraud intake form, then contacted TD’s security department to inform them directly of what she had unearthed. Soon, the bank discovered that Seck relied on Romanian documents not just for seven accounts but for 412 of them. The bank phoned local police and federal law enforcement to report that an insider appeared to be helping criminals cheat churches and TD.

–

The news delighted federal authorities: Since August 2018, they had been investigating a rash of thefts from church mailboxes around the country, and now they knew the bank accounts used by some of the crooks. Determining who these people were took weeks – Seck opened the accounts using false identities. But by April, agents had the name of at least one suspect and surveilled him as he looted a church mailbox. The next month, TD told law enforcement that they discovered another insider – this time at a Hollywood, Florida branch – who had helped some of the same people open bogus accounts there.

Nine months after TD’s tip, agents started rounding up conspirators, eventually arresting nine of them for crimes that netted more than $1.7 million in stolen checks. They all pleaded guilty to financial crimes except for Seck, who was convicted in February for bank fraud, accepting a bribe and other crimes. He was sentenced in June 2023 to three years in prison.

How could it happen? How could criminals engineer a year-long, multi-million dollar fraud just by relying on a couple of employees at two small bank branches in a scheme with victims piling up into hundreds?

The answer is because it’s easy. Crimes like these happen every day across the country. Scams facilitated by deceiving financial institutions – from international conglomerates to regional chains, community banks, and credit unions – are robbing millions of people and institutions out of billions and billions of dollars. At the heart of this unprecedented crime wave are so-called drop accounts – also known as “mule accounts”– created by street gangs, hackers and even rings of friends. These fraudsters are leveraging technology to obtain fake or stolen information to create the drop accounts, which are then used as the place to first “drop” and then launder purloined funds. In the process, criminals are breathing new life into one of modern history’s oldest financial crimes: check fraud.

To better understand the growing phenomenon of drop accounts and their role in far-reaching crime, the Evidence-Based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University joined with The Conversation in a four-month investigation of this financial underworld. The inquiry involved extensive surveillance of criminals’ interactions on the dark web and secretive messaging apps that have become hives of illegal activity. The investigation also examined video and audio tapes of the gangs, court documents, confidential government records, affidavits and transcripts of government wiretaps. The reporting shows:

- The technological skills of street gangs and other criminal groups are exceptionally sophisticated, allowing them to loot billions from individuals, businesses, municipalities, states and the federal government.

- Robberies of postal workers have escalated sharply as fraudsters steal public mailbox keys in the first step of a chain of crimes that ends with drop accounts being loaded with millions in stolen funds.

- A robust, anonymous online marketplace provides everything an aspiring criminal needs to commit drop account fraud, including video tutorials and handbooks that describe tactics for each bank. The dark web and encrypted chat services have become one-stop shops for cybercriminals to buy, sell and share stolen data and hacking tools.

- The federal government and banks know the scope and impact of the crime but have so far failed to take meaningful action.

“What we are seeing is that the fraudsters are collaborating, and they are using the latest tech,” said Michael Diamond, general manager of digital banking at Mitek Systems, a San Diego-based developer of digital identity verification and counterfeit check detection systems. “Those two things combined are what are driving the fraud numbers way, way up.”

Boom years for check fraud

Bank reports of cases of check fraud for both business and personal accounts have more than tripled in the past five years.

The growth is staggering. Financial institutions reported more than 680,000 suspected check frauds in 2022, nearly double the 350,000 such reports the prior year, according to the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, also known as FinCEN. Through internet transactions alone, swindles typically facilitated by drop accounts cost individuals and businesses almost $4.8 billion last year, a jump of about 60% from comparable fraud losses of more than $3 billion in 2020, the Federal Bureau of Investigation reported.

Plus, a portion of the estimated $64 billion stolen from just one COVID-19 relief fund went to gangsters who rely on drop accounts, according to a Congressional report and an analysis from the University of Texas at Austin. Criminals using drop accounts also hit the pandemic unemployment relief funds, which experienced improper payments of as much as $163 billion, the Labor Department found. Indeed, experts say the large sums of government money meant to combat economic troubles from COVID-19 fueled the rapid growth of drop account fraud, as trillions of dollars in rescue funds were disbursed in the form of wires and paper checks.

“There were a huge range of criminals who were trained in this during the pandemic,” said one banking industry official who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter. “A lot of them have grown up in the pandemic and seen that it is easy to make a lot of money with these schemes, with very little risk of prosecution.”

In the end, the financial world is witnessing a chaotic transformation of the fraud ecosystem of lawbreakers, victims and governments. The triangle of increased criminal sophistication, weak enforcement and an abundance of personal and business identities literally waiting to be snagged off the streets has fueled this cycle of larceny, one that shows no sign of slowing.

The cycle of fraud

–

The man in the hoodie suddenly appeared beside the mail carrier, who noticed a handgun stuffed in the young man’s waistband. “Give me your arrow key,” he said, according to court records.

An arrow key. The U.S. Postal Service’s universal key that opens blue public mailboxes, parcel lockers and apartment panels. The mail carrier struggled with the key chain attached to his belt as he attempted to appease the man robbing him.

“Hurry up,” the robber said. “There are kids around. I don’t want to hurt any kids.”

Finally, the carrier successfully removed his truck key and handed over the chain with the arrow key. The robber walked across Nowell Street and hopped into a waiting Jeep Grand Cherokee, which immediately took off.

Until recently, muggings of letter carriers were relatively rare, but they have grown in tandem with the explosion of drop account frauds. Stealing the key is often the first step in a cycle of crime that ends with banks and individuals scammed out of hundreds of millions of dollars.

These types of robberies only occurred 80 times in 2018, but now are almost a daily event. In fiscal 2022 and the first half of fiscal 2023, letter carriers were robbed 717 times, Postal Service statistics show. In 95% of those cases, the criminals only wanted the arrow key, according to Frank Albergo, president of the Postal Police Officers Association. “It’s completely out of control,” he said.

–

That is then turned over to another gang member, who uses the key to open public mailboxes and steal the contents. Those thefts can go on for days; one key opens as many as 600 boxes.

The mail thief then dumps the mail in the car and drives it to the gang members responsible for sorting. The piles of paper are separated, removing every check, credit card or other financial instrument as well as any document that can be used to steal an identity. Everything else is thrown away.

To open the drop accounts, others prepare IDs using the personal identity information stolen from the mail, hacked online, or purchased from a seller online.

Louis DeJoy, the postmaster general, acknowledged in Congressional testimony on May 15 that, despite the announcement, electronic locks would not be in place anytime soon. “This is a several year project,” he said.

How are the keys central to the drop account frauds? Once stolen by a gang member, the key is passed to another gang member who uses it to loot collection boxes and apartment panels. The thief then drives the stolen mail to gang members responsible for sorting. That group then separates every check, credit card or other financial and identity information.

Personal data found in stolen mail gives the gangs the names and addresses of potential victims. From there, the criminals search online databases – both legal and illegal – to gain access to dates of birth, Social Security numbers and other personal information, potentially including email addresses, driver’s licenses or passport numbers. This provides what in fraudsters’ slang is called fullz (pronounced fools), which stands for “full credentials.” It’s also the name used by the gangs for the person running online criminal marketplaces.

The fraudsters sometimes access secure systems at credit rating agencies that maintain financial and identifying information for millions of people. For example, our investigation spotted a video posted to an encrypted fraud channel on Telegram Messenger of someone signing in to what appears to be the TLOxp database, run by the credit rating agency TransUnion. That subscription-based system is intended primarily for companies, law enforcement, universities and other official organizations. But the data available on services like TLOxp is even more valuable to fraudsters. By using them, criminals enter a mecca of traditional fullz data plus employment history, unlisted phone numbers, assets, liens, judgments and other data.

The website on the fraudster video appears identical to TLOxp’s Advanced People Search product. In a statement, however, TransUnion suggested that the street gang posting the video instead designed their own website to make it appear as if they had obtained a TLOxp subscription when they had not. The company said the website on the video and the TLOxp site contain “subtle differences” that it would not identify and which are not apparent. Also, the second page shown on the video that TransUnion says was copied is only accessible for review through subscription. The company added that, “data security is TransUnion’s top priority,” and that it scans for references to TLOxp on the internet “to uncover any possible misuse of data.”

Access to this data makes opening drop accounts easy. Fraudsters often access bank websites by cell phone using disposable SIM cards; credentials in hand, the swindlers then establish drop accounts. Sometimes, they make a small deposit with clean money, but often that’s unnecessary: The gangs know which banks will keep an account open for a short period even if it holds no cash. In short order, the criminals receive a debit card delivered to a drop address – such as a rented or purchased house – and in short order, the bogus account is ready for use.

Meanwhile, other gang members have been doctoring the stolen checks. Check washing soaks off written ink by using a blend of acetone and gas-line antifreeze, creating a blank that can be filled out for many thousands of dollars. From there, the check is made payable to the name on the drop account, deposited, and the cash is removed at an ATM. There’s also a tactic called “check cooking,” where criminals scan the check and copy the signature using photo editing software. Then, they use that same software to add victim and banking information onto a stock check, and apply the signature, creating a forgery ready to be filled out for any sum.

–

Larger withdrawals sometimes require in-person bank visits, which brings more conspirators into the scam. Offering $200 to $300, so-called brokers recruit elderly or disabled people in hopes that bank tellers will be less likely to question their credibility. If needed, brokers give their hires new clothes and haircuts, then take them to the bank.

There, these “walkers” bring debit cards for drop accounts and fake IDs. Since there is nothing about them to indicate they are not an established customer, tellers cash checks based on the existing balance of stolen money in the drop accounts.

Often, walkers wear devices like AirPods connected to their phones, allowing the driver outside to provide real-time instructions in handling the withdrawal. According to an industry official who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue, banks have begun instructing branch employees to keep an eye out for people wearing earpieces, but tellers are not trained to stop sophisticated organized crime.

The marketplace

–

“Ya’ll in the game where you’re spending $250, and you’re making $30, $40, $50,000, and you n*****s complainin’, complainin’ about prices,” he said in the recording. “Every fullz in the game should be chargin’ ya’ll at least $1,000 for each slip that we sell. We’re in a thousand-dollar business. We ain’t in no $100 business, bro. So, stop (complaining).”

Moreover, he said, gang members were the ones risking prison. “We take all the risk for ya’ll to do what ya’ll will do. Ya’ll won’t even go to jail (unintelligible) cookin’ the slip up and dropping that sh*t in people account. …We can’t tell these crackers that we sold a slip to such and such and such for $250, so therefore you get 10 years. That’s not how that works, man. Pay the n****r that’s helping you eat!”

Needless to say, the carders’ attempt at price negotiation failed.

So it goes in the fraud marketplaces on Telegram, whose freewheeling channels are increasingly used by street gangs to peddle their wares and provide tips and techniques for committing bank fraud.

The Telegram channels often show photographs and videos of credit and debit cards for drop accounts obtained through stolen or fictitious identities. They also display other available goods, including details of existing drop accounts, ATM receipts showing the amount already deposited, stolen and counterfeit checks, tax refund checks, arrow keys and more. There are slick advertisements, complete with music and visual effects, for video tutorials priced around $500 that provide step-by-step instructions on how to open the accounts. And to entice skeptics, images often display piles of cash.

Prices vary based on the qualities of stolen or fake identities. Long-standing identities with good credit scores are worth more than freshly purloined ones. One Telegram fraud marketplace offered a nine-year-old identity with a perfect payment history, three open payment cards at three banks, and a credit score of 800. The price: $2,500.

–

The criminals also sell fake Social Security and ID cards that can be used by walkers at the banks. Videos on the platform demonstrate how the gangs can rapidly create sophisticated IDs – one fraud channel shows black lights illuminating otherwise invisible holograms on driver’s licenses, a security feature used by Transportation Security Administration screeners at airports to confirm an ID is real.

Deepfake software that creates talking, moving fictional people is also available. Now, live streams using newly sophisticated deepfakes help in “romance scams”, where fraudsters target lonely people to gain their affection; once victims are fooled into believing they have found romance online, the scammers convince them that they need money for some emergency. If the target agrees, the fraudster provides wiring instructions, often to a drop account.

The criminals also market on their Telegram channels through rap videos. The lyrics sometimes provide explanations of how the crimes are done and show piles of cash. One rap video we found is about debit card fraud. Called “Swipe It Up,” it provides details on committing the crime, including reminding listeners to confirm transactions when banks text their burner phones asking about possible fraudulent charges. Some of the lyrics are:

Swipe it up and get it goin’.I mean a lot.

I got a customer on the phone.

And if you get a text

You better not press no.

Swipe it up and get it goin’…

…Add it to the phone.

All I needed is a code.

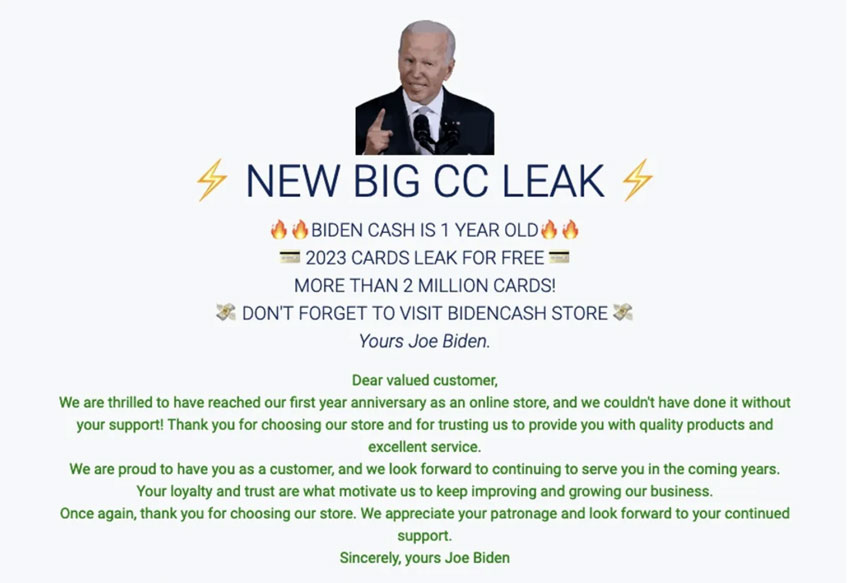

While street gangs and individual thieves have been primary drivers of drop account frauds since 2020, traditional hackers also remain big players. They sell the same information available on Telegram channels but use the dark web to do business.

Hackers don’t rob letter carriers, but rely on online theft of fullz data. A common technique is known as “digital skimming,” in which hackers access payment card information entered on checkout pages of online stores. But the easiest way for hackers to get their hands on fullz is to shop at one of two types of dark web marketplaces. The first is called “underground hacking websites,” which are used by sophisticated criminals who already stole online data and want more.

“Underground hacking website is where you can trade or sell or buy hacking, or you can talk to any other hackers,” said Hieu Minh Ngo, now a cybersecurity consultant in Vietnam who formerly ran a fraud market website until his 2013 arrest in the United States. “And then you can see lots of stuff, illegal stuff, like ATM card, stolen credit card, Social Security number, date of birth, driver’s license, fullz information.”

The second hacker marketplace is called carding forums, which operate more like Telegram fraud channels. They attract customers with limited or no hacking skills but who know how to commit banking and credit card fraud. One of the biggest such forums is Bidencash, which opened in March 2022. After starting with a low profile, its operators last June announced they had 7.9 million payment cards for sale. At its one-year anniversary, Bidencash celebrated by releasing 2.2 million more debit and credit cards.

(For the balance of this very interesting article please visit: https://theconversation.com/us/investigations/mailbox-robberies-drop-accounts-checkwashing-fraud-gangs-of-fullz/)