A major solar flare could cause havoc on Earth. NASA/SDO

–

In 1859, Earth was struck by the strongest solar storm in modern history. It was reported that aurora could be seen almost all the way to the equator – but it wasn’t all good news, as the spike also shorted out communications systems and even sparked fires in some telegraph stations. Now known as the Carrington Event, if a similar storm was to hit Earth today it could fry GPS satellites and knock out large sections of the power grid.

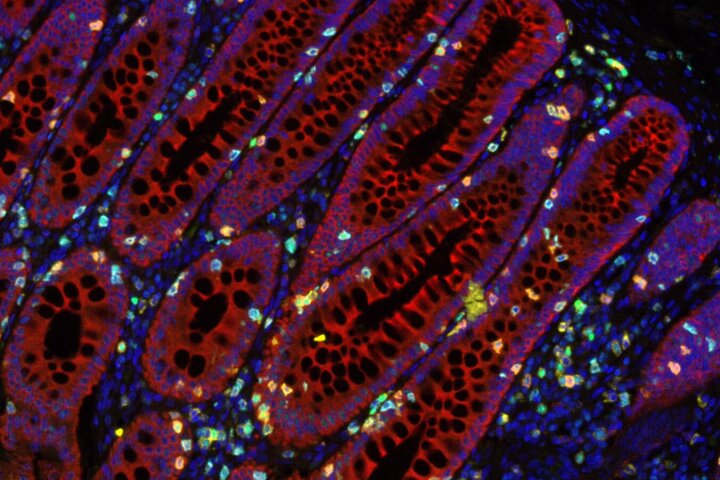

Of course, this wasn’t the Sun’s first rodeo – it was just the first to hit after human technology was advanced enough for us to notice. Scientists have since discovered several other examples, called Miyake events, within the last 15,000 years. These are found by searching for sharp spikes of radiocarbons in tree rings, or for measurements of elements like beryllium in ice cores.

“Radiocarbon is constantly being produced in the upper atmosphere through a chain of reactions initiated by cosmic rays,” said Edouard Bard, lead author of the study. “Recently, scientists have found that extreme solar events including solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) can also create short-term bursts of energetic particles which are preserved as huge spikes in radiocarbon production occurring over the course of just a single year.”

Now, scientists have found evidence of the most powerful solar storm on record – as much as 10 times more powerful than the Carrington event, and twice as strong as the previous record-holder, which blasted Earth in the year 774 CE. In the rings of ancient, partially fossilized trees in the French Alps, the team discovered an unprecedented radiocarbon spike dating back 14,300 years ago.

While some Miyake events seem to occur slower and may be attributed to other astronomical sources, the team says that the short timeframe of this spike, plus the fact it lines up well with a beryllium spike found in an ice core from Greenland, indicates a solar origin. Understanding what our Sun is capable of can help us prepare for future events.

“Radiocarbon provides a phenomenal way of studying Earth’s history and reconstructing critical events that it has experienced,” said Professor Tim Heaton, an author of the study. “A precise understanding of our past is essential if we want to accurately predict our future and mitigate potential risks. We still have much to learn. Each new discovery not only helps answer existing key questions but can also generate new ones.”

The research was published in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A.

Source: University of Leeds

–