Scientists finally find out how these water bears withstand extreme stress. Depositphotos –

Scientists finally find out how these water bears withstand extreme stress. Depositphotos –

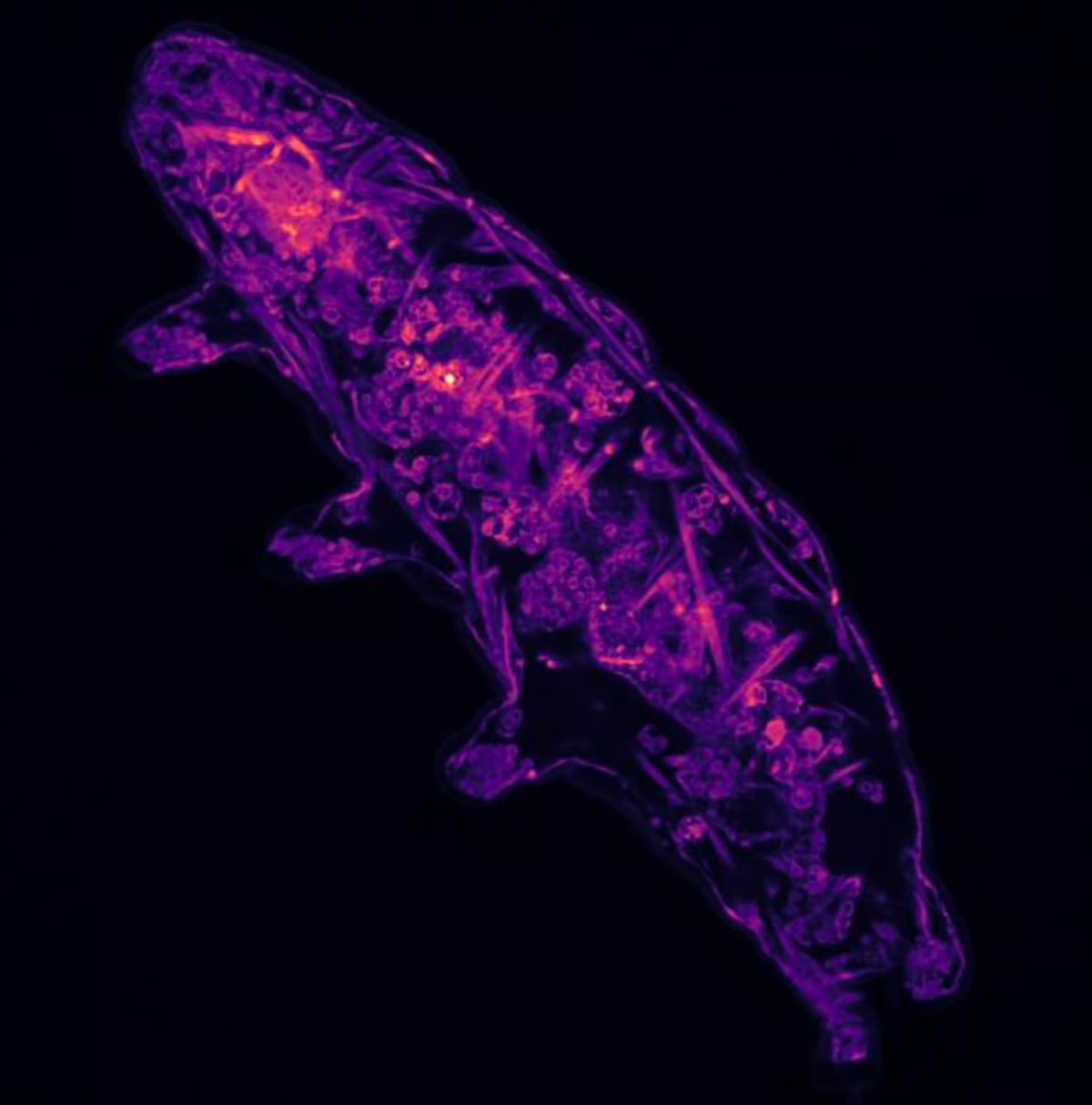

The eight-legged aquatic invertebrates are well known to be able to withstand intense heat, cold and dry conditions, entering a dehydrated state known as a tun, with the microscopic tardigrade shrinking to a third of its already small size and curling into a ball. In this dormant state of extremely slow metabolism – a form of cryptobiosis called anhydrobiosis – the animal can live for extended periods, only to emerge from self-preserving hibernation to resume normal activities.

While an earlier study had uncovered the biological processes that enabled this state of suspended animation, what triggered this state has remained a mystery.

Now, a team led by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Marshall University researchers has identified the molecular switch that begins the tardigrade’s transformation.

The scientists exposed a model tardigrade species, Hypsibius exemplaris, to extreme conditions – freezing temperatures of -80 °C (−112 °F), high hydrogen peroxide levels and strong salt and sugar solutions – in order to trigger the tun transformation. They found that a molecular sensor built on the amino acid cysteine was key to the animal’s ability to switch this state on and off as required.

In the extreme conditions, the tardigrades were found to have an accumulation of free radicals – oxygen atoms or molecules – inside cells, stealing electrons from other atoms. In high concentration, free radicals cause a great deal of oxidative stress, however, for the tardigrades they act as a trigger for initiating anhydrobiosis.

As the environment returned to more hospitable conditions, this process was reversed and the tardigrade received the molecular message that it was safe to return to its original, fully functioning state.

However, when the scientists blocked cysteine in the animals, they were unable to enter their life-saving dormant state, revealing the important interplay between the combination of oxygen free radicals and this amino acid ‘switch’.

“We have revealed that tardigrade survival is dependent on reversibly oxidized cysteines coordinating the entrance and emergence from survival states in a highly regulated manner,” the researchers wrote in the study. “Through implementation of EPR and redox library screens, we have demonstrated that intracellular release of ROS is essential for tun formation.”

The research was published in the journal PLOS One.

Sources: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Marshall University, via EurekAlert!

–