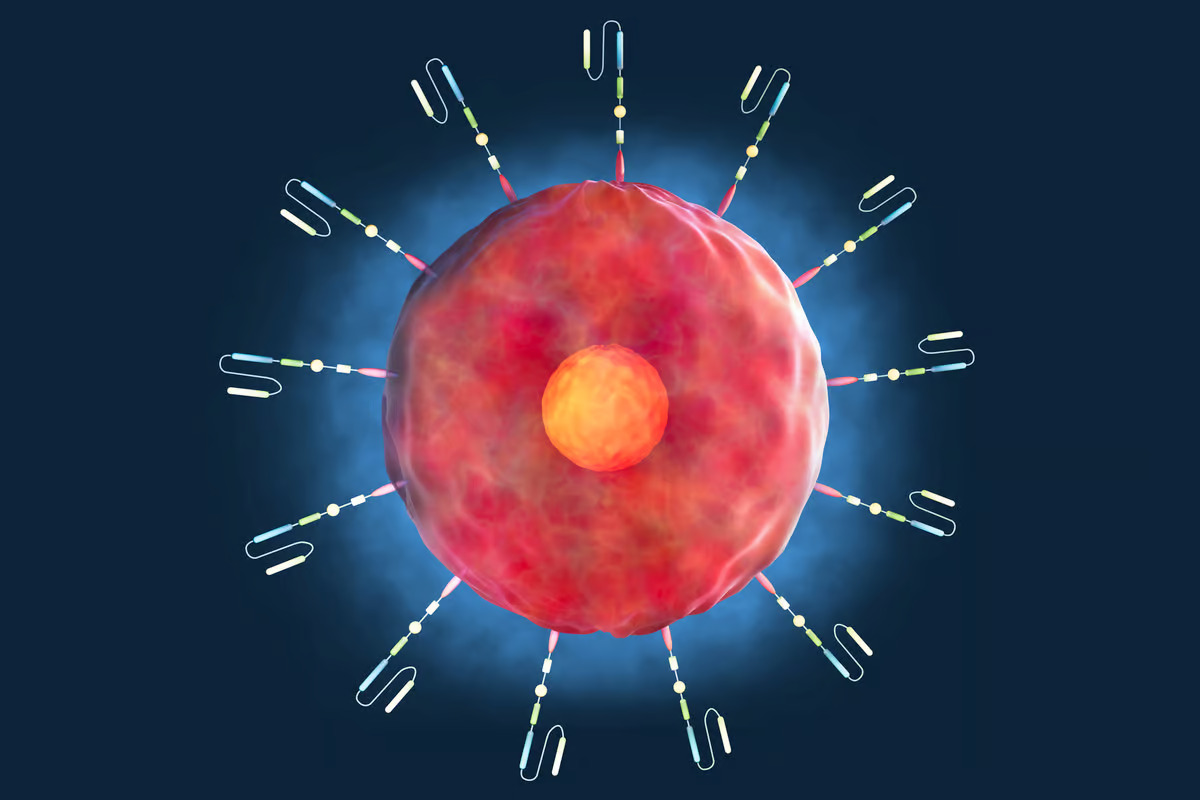

T cells fulfill crucial roles in the body’s immune system. They can act as ‘killer’ cells, attacking cells infected with a virus or other pathogen, or as ‘helper’ cells, supporting B cells in producing antibodies. They can also be engineered to fight cancer. In CAR T-cell therapy, a patient’s own T cells are modified in the lab to produce surface proteins called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that recognize and bind to specific antigens on the surface of cancer cells, which they then destroy.

In a new study, researchers from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), New York, discovered that these CAR T cells can be reprogrammed to target senescent cells, thought to be involved in aging and many of the diseases encountered in later life.

Simply put, senescent cells are cells that have stopped multiplying but haven’t died off. They linger in the body and continue to release chemicals that can trigger inflammation. As people age and their immune systems become less effective at clearing senescent cells, they accumulate, generating chronic inflammation – sometimes referred to as ‘inflammaging’ – that can lead to age-related disease.

Aware that senescent cells carry the cell-surface protein urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), the researchers first examined the association between the protein and aged tissues. RNA sequencing in young and old mice revealed that the expression of Plaur, the gene encoding uPAR, was upregulated in several organs in 20-month-old animals compared to three-month-olds. (By the way, a three-to-six-month-old mouse is equivalent to a 20-to-30-year-old human; a mouse between 18 and 24 months old is equivalent to a human aged 56 to 69.)

Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed an age-associated increase in uPAR protein in the liver, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and pancreas. Examining datasets of human pancreatic tissue collected from young (zero-to-six-year-old) and aged (50-to-70) individuals, the researchers found that uPAR was expressed in senescent cells that accumulate with age. Taken together, these results indicated that the levels of uPAR-positive senescent cells increased with age and that most senescent cells found in aged tissues expressed uPAR.

The researchers next created uPAR-targeting CAR T cells, which they tested on naturally aged (18-to-20-month-old) mice. After injection with a single dose, the CAR T-cell-treated mice were healthier than the control animals. They had improved metabolism, including significantly decreased fasting blood glucose levels and better insulin sensitivity, and improved exercise capacity. uPAR CAR T cells also reduced the number of uPAR-positive cells in the tissues, with an accompanying decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines. The treatment was well-tolerated by the mice and not toxic.

When three-month-old mice were given a dose of uPAR-targeting CAR T cells, the researchers noticed that the CAR T cells remained over the animal’s natural lifespan despite the lower numbers of uPAR-positive cells in the young mice. The CAR T cells were detectable in the spleens and livers of treated mice 12 months after the initial single infusion. The treatment also appeared to prevent metabolic decline as the mice aged.

After feeding young mice a high-fat diet, a model of obesity and metabolic stress, the researchers gave them a dose of uPAR CAR T cells. Post-treatment, the mice displayed significantly lower body weight, improved fasting blood glucose levels and insulin sensitivity, and reduced numbers of senescent cells in the pancreas, liver and adipose tissue that persisted through the monitoring period. The treatment also acted prophylactically to prevent metabolic dysfunction, raising the possibility that targeting senescent cells with CAR T cells may have therapeutic benefit in humans.

“If we give it to aged mice, they rejuvenate,” said Corina Amor Vegas, lead and corresponding author of the study. “If we give it to young mice, they age slower. No other therapy right now can do this.”

An obvious benefit to the novel treatment is its longevity, as evidenced by the researcher’s experiments using uPAR CAR T cells on young mice.

“T cells have the ability to develop memory and persist in your body for really long periods, which is very different from a chemical drug,” Amor Vegas said. “With CAR T cells, you have the potential of getting this one treatment, and then that’s it. For chronic pathologies, that’s a huge advantage. Think about patients who need treatment multiple times per day versus you get an infusion, and then you’re good to go for multiple years.”

The researchers are now looking at whether CAR T cells let mice live not only healthier but longer.

The study was published in the journal Nature Aging. Source: CSHL

–