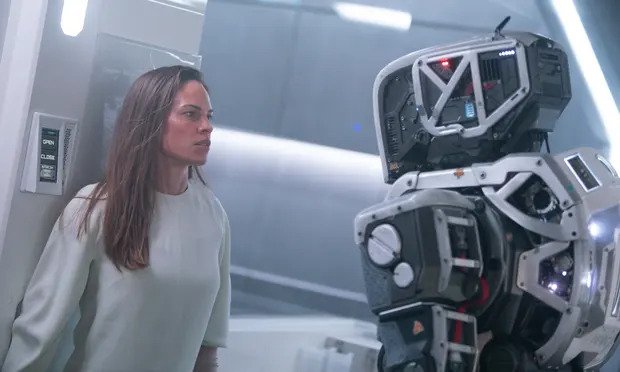

Hilary Swank in AI thriller I Am Mother (2019). Photograph: Netflix

Hilary Swank in AI thriller I Am Mother (2019). Photograph: Netflix

–

By John Naughton

Last modified on 2021 Dec 25

–

In the first of his four (stunning) Reith lectures on living with artificial intelligence, Prof Stuart Russell, of the University of California at Berkeley, began with an excerpt from a paper written by Alan Turing in 1950. Its title was Computing Machinery and Intelligence and in it Turing introduced many of the core ideas of what became the academic discipline of artificial intelligence (AI), including the sensation du jour of our own time, so-called machine learning.

–

From this amazing text, Russell pulled one dramatic quote: “Once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control.” This thought was more forcefully articulated by IJ Good, one of Turing’s colleagues at Bletchley Park: “The first ultra-intelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.”

–

Russell was an inspired choice to lecture on AI, because he is simultaneously a world leader in the field (co-author, with Peter Norvig, of its canonical textbook, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, for example) and someone who believes that the current approach to building “intelligent” machines is profoundly dangerous. This is because he regards the field’s prevailing concept of intelligence – the extent that actions can be expected to achieve given objectives – as fatally flawed.

AI researchers build machines, give them certain specific objectives and judge them to be more or less intelligent by their success in achieving those objectives. This is probably OK in the laboratory. But, says Russell, “when we start moving out of the lab and into the real world, we find that we are unable to specify these objectives completely and correctly. In fact, defining the other objectives of self-driving cars, such as how to balance speed, passenger safety, sheep safety, legality, comfort, politeness, has turned out to be extraordinarily difficult.”

That’s putting it politely, but it doesn’t seem to bother the giant tech corporations that are driving the development of increasingly capable, remorseless, single-minded machines and their ubiquitous installation at critical points in human society.

This is the dystopian nightmare that Russell fears if his discipline continues on its current path and succeeds in creating super-intelligent machines. It’s the scenario implicit in the philosopher Nick Bostrom’s “paperclip apocalypse” thought-experiment and entertainingly simulated in the Universal Paperclips computer game. It is also, of course, heartily derided as implausible and alarmist by both the tech industry and AI researchers. One expert in the field famously joked that he worried about super-intelligent machines in the same way that he fretted about overpopulation on Mars.

But for anyone who thinks that living in a world dominated by super-intelligent machines is a “not in my lifetime” prospect, here’s a salutary thought: we already live in such a world! The AIs in question are called corporations. They are definitely super-intelligent, in that the collective IQ of the humans they employ dwarfs that of ordinary people and, indeed, often of governments. They have immense wealth and resources. Their lifespans greatly exceed that of mere humans. And they exist to achieve one overriding objective: to increase and thereby maximise shareholder value. In order to achieve that they will relentlessly do whatever it takes, regardless of ethical considerations, collateral damage to society, democracy or the planet.

One such super-intelligent machine is called Facebook. And here to illustrate that last point is an unambiguous statement of its overriding objective written by one of its most senior executives, Andrew Bosworth, on 2016 Jun 18: “We connect people. Period. That’s why all the work we do in growth is justified. All the questionable contact importing practices. All the subtle language that helps people stay searchable by friends. All of the work we have to do to bring more communication in. The work we will likely have to do in China some day. All of it.”

As William Gibson famously observed, the future’s already here – it’s just not evenly distributed.

What I’ve been reading

Pick a side

There Is no “Them” is an entertaining online rant by Antonio García Martínez against the “othering” of west coast tech billionaires by US east coast elites.

Vote of confidence?

Can Big Tech Serve Democracy? is a terrific review essay in the Boston Review by Henry Farrell and Glen Weyl about technology and the fate of democracy.

Following the rules

What Parking Tickets Teach Us About Corruption is a lovely post by Tim Harford on his blog.

–

–

We’ve hit our goal!

For 10 years, the Guardian US has brought an international lens with a focus on justice to its coverage of America. Globally, more than 1.5 million readers, from 180 countries, have recently taken the step to support the Guardian financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent. We couldn’t do this without readers like you.

With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we can set our own agenda and provide trustworthy journalism that’s free from commercial and political influence, offering a counterweight to the spread of misinformation. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favor. It is reader support that makes our high-impact journalism possible and gives us the emotional support and motor energy to keep doing journalism that matters.

Unlike many others, Guardian journalism is available for everyone to read, regardless of what they can afford to pay. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of global events, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action.

We aim to offer readers a comprehensive, international perspective on critical events shaping our world. We are committed to upholding our reputation for urgent, powerful reporting on the climate emergency, and made the decision to reject advertising from fossil fuel companies, divest from the oil and gas industries, and set a course to achieve net zero emissions by 2030.

Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism and sustains our future. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

Most viewed